Liars

A fictional travelogue; four minutes to read.

Clemens, his eight-year-old son Sawyer and I are riding the Amtrak out of Philadelphia bound for Washington, D.C. We are crowded together in a cubby of a seating area. We have two hours until Union Station. Time enough to ignore each other—or introduce ourselves.

Under his thin green jacket, the father is muscled. Close-cropped black hair looks home-barbered. His son is long overdue for a haircut. Their shoes, badly scuffed, are laced with knotted, mismatched—one black, one brown—shoelace segments.

Sawyer is just a few years younger than my high school history students. Soon he’ll be learning about the U.S. Constitution, checks and balances, our republican form of democracy.

He will be old enough to witness for himself unchecked and unbalanced presidential lying. The day after Trump told the nation that he is 6’3” and 215 pounds, the basketball team boys in my class started mocking him. They compared him to photos of NBA stars, and decided Trump is more like 5’9” and 250 pounds.

None of my students were surprised. I had prepared them with my lectures. “Lying is a bipartisan presidential tradition. President Thomas Jefferson lied about the real purpose of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which was territorial expansion, not scientific exploration. President Lyndon Johnson lied about U.S. naval ships being attacked by the North Vietnamese in the Gulf of Tonkin. President George Bush lied about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq.”

Trump’s lies are so commonplace, and common, I’ve almost stopped paying attention to his gaslighting. My days are spent paying bills, talking with my kids, gassing up the car, reading, cooking, cleaning. It’s easy to look the other way.

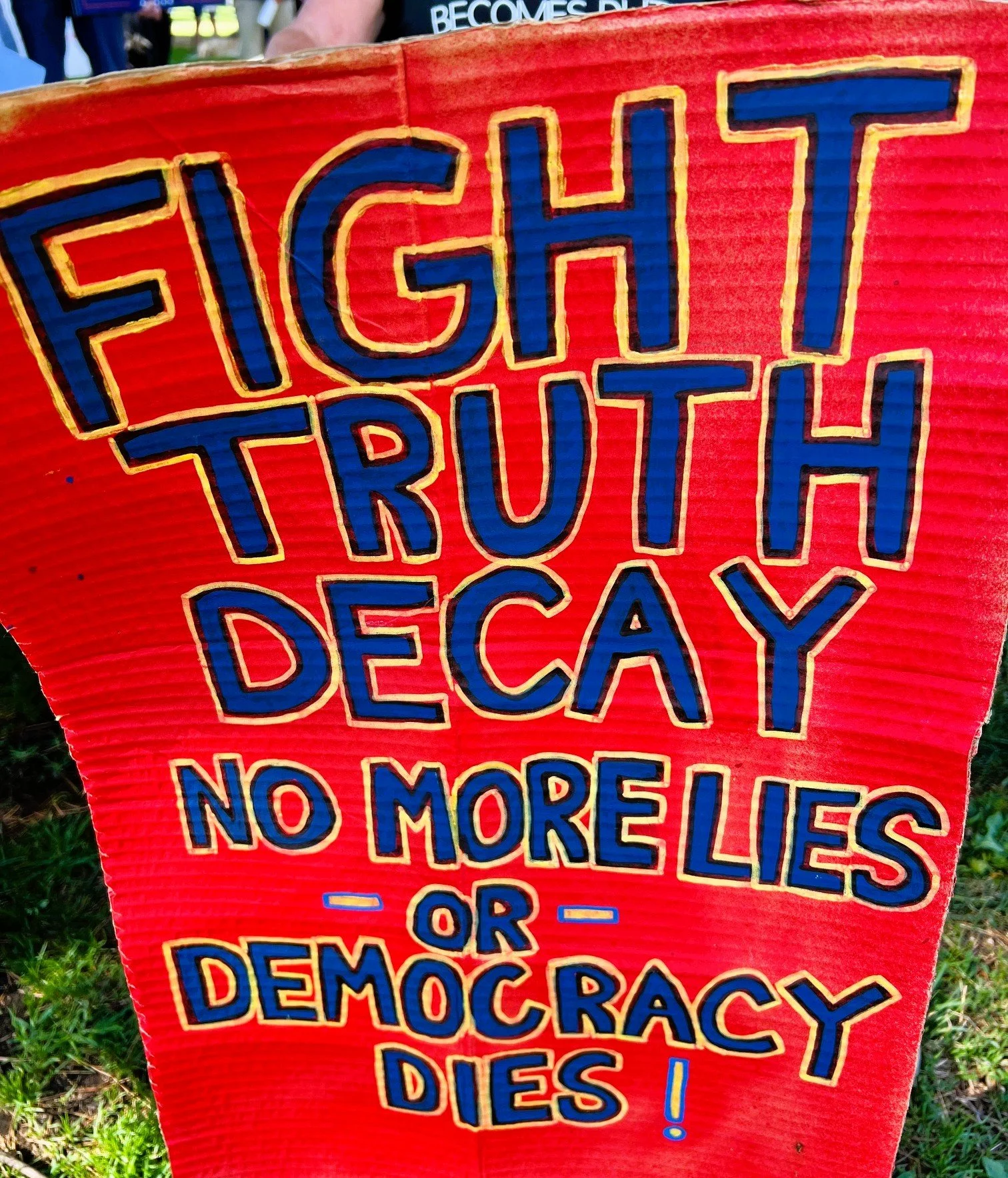

When my government has to be forced to tell the truth, sustained resistance is hard. It’s one of Trump’s most potent political powers. Weaponized lying. He’s obese with it.

On the days my classes talk about good citizenship, integrity of the ballot box, patriotism over party, the rule of law, their civics textbook is at odds with their reality. I need extra glasses of water to fend off my dry mouth.

While Sawyer is off exploring the train, Clemens is talking. His breath fogs the train window, blurring the passing winter landscape. His words move me from my schoolroom into his world.

“I promised Sawyer for his birthday, he turned eight last week, that I would take him to see the White House. He’s been wanting to see where the president lives ever since he learned the presidents in school.”

“I called in sick at work. Told his school the same.”

My chest tightens.

I ask, “So, will Sawyer’s school work suffer from missing school?”

“It don’t matter. I’ll tell you that. I had to do it.”

“Adults don’t do right by him.” His muscles briefly tense, his hands grip the armrests, then his eyes mist up. “His mom left us when he was five. His uncles say they’ll buy him things, and then don’t. For his birthday, his aunt said she’d bake him a chocolate cake, but she never did.”

Coming down the aisle, Sawyer is moving towards us, his eyes darting everywhere. The train lurches, and Sawyer laughs.

“I promised him this trip. He’s gotta have some grownup he can trust.”