Poblanos

A fictional travelogue; four minutes to read.

Our dinner party hostess—my semi-reclusive, but always helpful neighbor—chose an embroidered Mexican peasant dress to wear. For drinks and hors d’oeuvres, taquitos served on green glassware from Puebla. Place settings with Talavera napkin rings.

“I just got back from a lovely week in Puebla,” she begins the evening. “I felt a genuine kinship with the Mexican people. Maybe someone on my family tree was Hispanic.”

As her travel report unfolds, she is glowing like a young bride. We hear that she dined at Puebla’s most authentic restaurants, strolled cobbled neighborhoods unknown to gringos and made lifelong friends of “the locals.” Apparently, her new friends failed to mention that “the locals” call themselves Poblanos—not locals, natives or aboriginals.

I don’t blame her for wanting an audience. As a schoolteacher, I enjoy captive audiences—without cooking dinner.

Travel storytelling is a way of remembering, and since none of us can remember everything that we want, it just makes sense to remember the best parts. We all buff up our life stories.

High school textbooks are humble reminders that even my best sources have filtered, omitted, forgotten, embellished the history I pass along to my students. Even firsthand sightseeing is as much not seeing as seeing.

I do it all the time. Looking past what is ugly, tiptoeing around what is stinky, ignoring the commonplace.

I’ve spent time in Puebla, but what I know of it is episodic, spotty, frayed. Just as what she and I know about our neighborhood, where we are locals, is fragmentary and incomplete.

In Puebla, the artisanal basket-sellers bordering the zócalo captivate me, but the peddlers pushing plush toys made in China not so much. I savor the aromas from grilling tacos al pastor at a curbside stand and walk past the equally popular KFC.

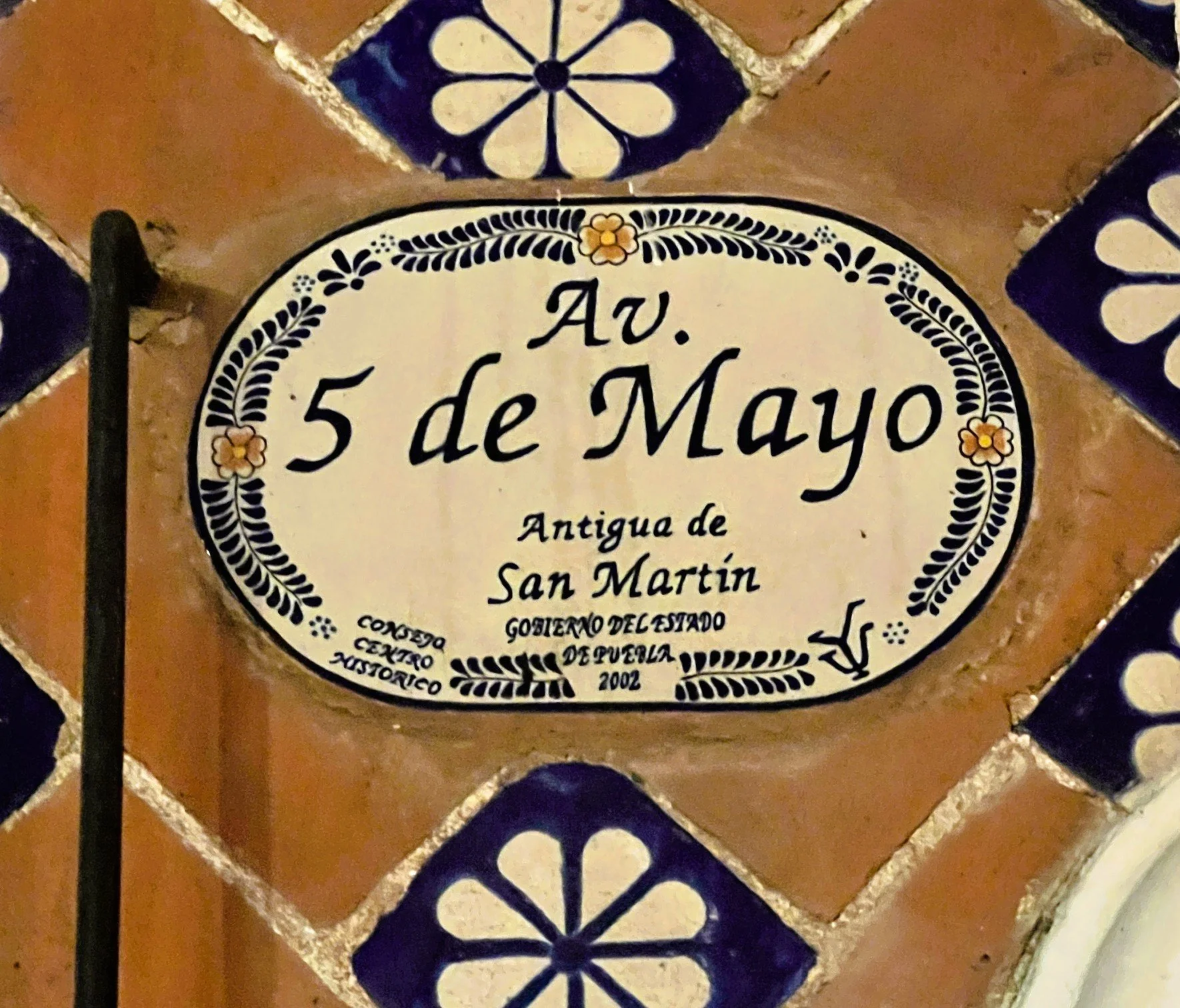

As our hostess holds forth about her week in Puebla, my mind turns inward. I transport myself to a bench on Cinco de Mayo street. Plantings, colonial-era lampposts, food sellers, buskers. It is brisk with people of all ages including a sizeable number in strollers. Cars are banned.

In a small café, my extra thick Mexican hot chocolate comes with a sugary roll. I soak up the local scene.

Near me, eight Poblanos are having snacks, drinks, laughing, talking over each other, playing a card game. A local tradition for young professionals? An office team-building exercise? A mixer for singles?

The couple across the way is in love. Between bites of food, they hold hands. Every intruder to their dining—two young men selling hand-painted postcards, a mute beggar, the flower girl—opens their wallets. Love is charitable, I guess.

I can take in Puebla’s charms without bothering these Poblanos. Even if I spoke better Spanish, I’m not entitled to their time. They’re busy; their lives are not my playground.

In any event, there’s no such thing as locals, only individuals at dinner parties. The dining room has turned quiet, rapt. I’m pulled out of my reverie.

“So after Eduardo and I finished our second cerveza—the local ale is called 1821, the year of Mexican Independence, he offered to walk me back to my hotel. At my age, I was flattered,” she winks a half-giggle. Empty tequila shot glasses are crowded around her.

Poblano or neighbor, mostly we keep our secrets secret.